After leaving South Georgia on 6 March, we "set sail" toward the Tristan island group, which we would reach on 11 March. Tristan is the most remote human habitation on the planet. It is a British territory administered from St. Helena Island (where Napoleon was imprisoned). For an interesting overview of the history, complete with maps, pictures and other information, I recommend the Tristan da Cunha website. The only way to get there is by sea and it took four days. Tristan is REMOTE. There is no airport – or place to put one.

I was unable to get good pictures of the myriads of birds that followed us throughout our journey. This is a giant petrel. There was a day or two in our journey between South Georgia and Tristan that we didn't see many birds. When we began to see them again, we knew we were nearing land.

The first land that we sighted of the Tristan group was Gough Island. It was very early in the morning and I didn't even try to get a picture of it.

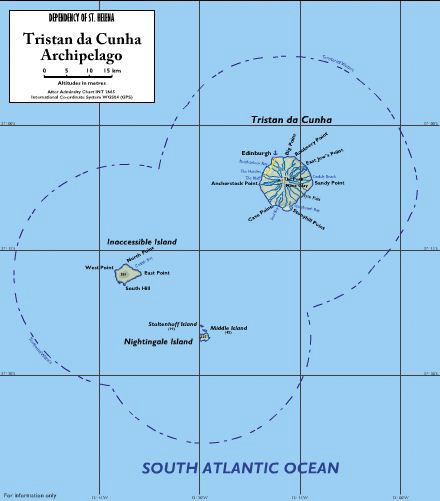

It will help to include an overview of the Tristan Archipelago. All of the islands are volcanic and Tristan itself is still an active volcano. It is the only one of the islands that has a permanent settlement.

Gough Island is not shown in this map as it is farther south.

Tristan clearly shows its volcanic origin.

Tristan clearly shows its volcanic origin.

The four major islands of the archipelago, Tristan, Nightingale, Inaccessible and Gough, were all formed as the African plate moved over a hot spot beneath the ocean floor.

Tristan is the newest of the islands by a large margin – an estimated 200,000 years old. Its most recent eruption was in 1961.

The seas were not immediately conducive to a landing, so we cruised around the island hoping that the weather would ameliorate.

Edinburgh

of the Seven Seas is the only habitation on Tristan. When the volcano

erupted in 1961, the eruption was perilously close to the settlement It was centered on the cinder cone shown

to the left of this picture.

All of the residents were evacuated, first to Nightingale Island and

later to England. When the eruption subsided the vast majority

of islanders opted to return – much to the surprise of the British

adminstration. The lava flows didn't

reach the village proper although they did destroy the harbor and a

fish processing facility.

Edinburgh

of the Seven Seas is the only habitation on Tristan. When the volcano

erupted in 1961, the eruption was perilously close to the settlement It was centered on the cinder cone shown

to the left of this picture.

All of the residents were evacuated, first to Nightingale Island and

later to England. When the eruption subsided the vast majority

of islanders opted to return – much to the surprise of the British

adminstration. The lava flows didn't

reach the village proper although they did destroy the harbor and a

fish processing facility..jpg) Around

the corner from the village is the agricultural area known as "the potato patches." The buildings are used to

store agricultural equipment or as holiday houses.

Around

the corner from the village is the agricultural area known as "the potato patches." The buildings are used to

store agricultural equipment or as holiday houses..jpg) By

the time we finished our circuit of Tristan, the weather was still not

suitable for landing. Nevertheless there were some Tristaners who needed

to travel to Cape Town. All ships that call at the island agree

to take on passengers. Opportunities to leave are extremely limited,

and since the weather might have been even worse later, the locals came

out in this sturdy boat to board.

By

the time we finished our circuit of Tristan, the weather was still not

suitable for landing. Nevertheless there were some Tristaners who needed

to travel to Cape Town. All ships that call at the island agree

to take on passengers. Opportunities to leave are extremely limited,

and since the weather might have been even worse later, the locals came

out in this sturdy boat to board.

It was fascinating, and scary, to watch how they scrambled aboard the ship (the photograph does not adequately convey the rough water). There was one child traveling with his mother to visit his father working in Cape Town. He was literally thrown from this boat to waiting arms on the ship's landing platform.

The adults were hauled on board with even less ceremony. In addition to the mother and child, there was a honeymooning couple relocating to new jobs in France, and a tourist from South Africa who had been visiting for about a month.

After loading our fellow travelers, our leaders decided to travel to Nightingale Island to see if we might be able to land there. This picture gives a better image of the state of the sea.

I'm standing on deck 4 overlooking deck 3. As the ship fell into the trough between the wave crests, there were tremendous splashes. This was by no means the largest splash I saw before finally going inside to dry off. It was an exciting ride even though the sea looks quite calm.

.jpg) This

was as close to Inaccessible

Island as we got. The island received its name because of the difficulty

reaching its interior. It wasn't until 1982 that an expedition penetrated to the interior for scientific study.

This

was as close to Inaccessible

Island as we got. The island received its name because of the difficulty

reaching its interior. It wasn't until 1982 that an expedition penetrated to the interior for scientific study. We

reached Nightingale Island and cruised around it, but the seas never

allowed us to land. Since our visit there has been a

shipping disaster that caused the death of numerous rockhoppers

and untold numbers of other wildlife. It has also severely impacted

the Tristan fishery, which is a major source of island income.

We

reached Nightingale Island and cruised around it, but the seas never

allowed us to land. Since our visit there has been a

shipping disaster that caused the death of numerous rockhoppers

and untold numbers of other wildlife. It has also severely impacted

the Tristan fishery, which is a major source of island income. Nightingale

is the breeding grounds of numerous birds including the Northern Rockhopper

penguin. Take my word for it, they are in this picture along the top

of the guano-stained rock.

Nightingale

is the breeding grounds of numerous birds including the Northern Rockhopper

penguin. Take my word for it, they are in this picture along the top

of the guano-stained rock.The buildings are cabins where islanders may stay when they visit here to "get away from it all."

When Tristan's volcano erupted the villagers evacuated to Nightingale until they could be taken to England. After the eruption, almost all of the islanders chose to return to their remote home, much to the surprise of their countrymen.

We

had acknowledged between ourselves before we even signed up for the

trip that it was a real possibility that all we would be able to do

was wave at Tristan in passing.

We

had acknowledged between ourselves before we even signed up for the

trip that it was a real possibility that all we would be able to do

was wave at Tristan in passing.

After spending the night on the ship off Edinburgh, the morning of our 2nd day we did get on shore. The captain of our ship had been to the island five times before and this was the first time he was able to land! We were very lucky! Of the two cruise ships that called at Tristan in the 2009/2010 season, ours was the only one that actually landed visitors. (If you follow the link, you can find Jim in the coffee shop photo and the two of us with our backs to the camera leaving the harbor in the Zodiac.)

As is evident in this picture, the passenger facilities at Tristan are pretty basic! I can't even imagine how the heavy construction equipment was ever landed, but it was there. Most of the islanders even have cars or trucks!

The paper I'm holding is the local Lexington News-Gazette. Every year they ask travelers to take a copy on vacation and submit pictures. Yes, this one got published and we had our 15 minutes of fame.

Our "penguin collectors," by the way, were able to arrange a special tour to the penguin rookery on Tristan. They were thrilled to get much better pictures of the Rockhoppers than the one I have above from Nightingale.

Tristan's

economy is based on fishing. Their cash "crop"

is rock lobster. As a result boats are much in evidence.

Tristan's

economy is based on fishing. Their cash "crop"

is rock lobster. As a result boats are much in evidence.These are spares secured against the strong winds that are common here.

In the old days these boats were made from driftwood and sealed and painted canvas. Nowadays they are made of fiberglass.

The community even owns a fishing trawler, which makes occasional jaunts to Cape Town to market the lobsters.

Another

mainstay of the economy is stamps. Tristan postal issues are highly

sought after. If collectors could only obtain stamps by coming to the

island, they would be quite rare indeed, but the island does a thriving

internet business.

Another

mainstay of the economy is stamps. Tristan postal issues are highly

sought after. If collectors could only obtain stamps by coming to the

island, they would be quite rare indeed, but the island does a thriving

internet business.In spite of its remoteness, the community is self-sustaining. It has all the "conveniences" of most other places including an internet cafe with a satellite link. The one thing that it lacks is credit card service. Perhaps this is not a bad thing. They also lack elaborate police and criminal justice structures as they are not needed here.

There is a basic hospital to care for most ills, but for complicated procedures such as joint replacements, islanders must travel to Cape Town.

Most of the islanders are well-traveled, in spite of the difficulty. Many have been to England either for vacation or education and our local guide had been to the US as well.

The

day we visited the schools had a holiday. These children are hanging

out at the Community Center. Inside the islanders had set up a cooperative

shop to sell souvenirs. I bought a knitted wool cap to match the scarf

I purchased at Stanley.

The

day we visited the schools had a holiday. These children are hanging

out at the Community Center. Inside the islanders had set up a cooperative

shop to sell souvenirs. I bought a knitted wool cap to match the scarf

I purchased at Stanley. Our

town tour guide explained that each family was allowed two cows. They

could also have sheep and chickens. Our guide introduced us to one of

his cows – his daughters had named her Angel. I assume that Angel's

progeny provided beef for the family rather than Angel herself!

Our

town tour guide explained that each family was allowed two cows. They

could also have sheep and chickens. Our guide introduced us to one of

his cows – his daughters had named her Angel. I assume that Angel's

progeny provided beef for the family rather than Angel herself!There were also donkeys on the island which had once been used to carry produce back from the agricultural potato patches. When the island imported trucks the donkeys were out of a job. Most families have their own car or truck in spite of the small size of the settlement. There are numerous dogs, mostly border collies, but no cats, which are forbidden due to the rare birds on the island.

.jpg) After

the town tour we had two options: take a tour to the Potato Patches

or climb the 1961 cinder cone. As in the Falklands, Jim & I decided

to split up to get the best coverage. He visited the patches and I headed

up the cinder cone.

After

the town tour we had two options: take a tour to the Potato Patches

or climb the 1961 cinder cone. As in the Falklands, Jim & I decided

to split up to get the best coverage. He visited the patches and I headed

up the cinder cone.Each "patch" is delineated by the volcanic rock that is so abundant on the island. The same rock is used within each patch to separate different crops. The islanders have built sheds and cabins, some quite elaborate, to use for their agricultural pursuits.

Even

given the relative newness of the eruption, the cinder cone is being

colonized by plants – ferns, mosses and grasses.

This in spite of the fact that it is still venting steam at times.

Even

given the relative newness of the eruption, the cinder cone is being

colonized by plants – ferns, mosses and grasses.

This in spite of the fact that it is still venting steam at times. One of the many attractions of traveling with Elderhostel

(now Road Scholar) is the variety of people we meet. Our guide, Cherifa,

although she may not have been one of the highlighted speakers, was

fascinating. She was born in Algeria and later taken to an

orphanage in France. There she studied languages at the Sorbonne. She

became a simultaneous translator at the UN in New York and is now leading

Road Scholar groups all over the world. We would love to travel with

her again.

One of the many attractions of traveling with Elderhostel

(now Road Scholar) is the variety of people we meet. Our guide, Cherifa,

although she may not have been one of the highlighted speakers, was

fascinating. She was born in Algeria and later taken to an

orphanage in France. There she studied languages at the Sorbonne. She

became a simultaneous translator at the UN in New York and is now leading

Road Scholar groups all over the world. We would love to travel with

her again.Cherifa is pictured here atop the cinder cone overlooking Edinburgh.

Returning

to the ship was an exciting experience. The wind had picked up as well as

the swell. Climbing from a wild Zodiac that is slamming against the

ship's landing stage was a heart-stopping experience requiring good

timing and a lot of help. We were glad that all made it back safely.

Returning

to the ship was an exciting experience. The wind had picked up as well as

the swell. Climbing from a wild Zodiac that is slamming against the

ship's landing stage was a heart-stopping experience requiring good

timing and a lot of help. We were glad that all made it back safely.

Even so it was quiet enough (compared to the rest of the trip) that the ship's staff set up a grill on deck and barbecued fresh-caught fish and the local rock lobsters.

It would have been lovely to be able to eat outside more often, but the conditions did not permit it more than about three days.

Click on your browser's "back" button to return to the index or click to continue to South Africa.